Text Essay 3

Buddhist Places

Introduction: Buddhism’s Most Sacred

Place

In the centuries and millennia following the death of the Buddha,

his teachings spread across Asia and, more recently, the western

world. Over time, the Buddha’s dharma

evolved so that a Buddhist in Japan might find little in common

with a follower in Vietnam, Thailand, Sri Lanka, Tibet, or Los Angeles.

Nonetheless, however they find it, all Buddhists aspire to achieve

nirvana,

just as Siddhartha Gautama did beneath the Bodhi

tree at Bodh Gaya, in northeastern India, all those years ago.

About eight centuries ago, however, Buddhism disappeared from India

even as it thrived throughout the rest of Asia. Although pilgrims

continued to travel to this holy site, temples and stupas

built to commemorate this moment of enlightenment were buried under

windblown sands. The Bodhi tree died away.

In

the nineteenth century, the British rulers of India began to restore

the temple complex at Bodh Gaya. They cleared away the sand and

planted a cutting of a descendant of the bodhi tree that had been

nurtured for millennia in Sri Lanka, far to the south. Devout Buddhists

from Burma (Myanmar) completed the restoration, and today Bodh Gaya

hosts devoted pilgrims from across the globe. In

the nineteenth century, the British rulers of India began to restore

the temple complex at Bodh Gaya. They cleared away the sand and

planted a cutting of a descendant of the bodhi tree that had been

nurtured for millennia in Sri Lanka, far to the south. Devout Buddhists

from Burma (Myanmar) completed the restoration, and today Bodh Gaya

hosts devoted pilgrims from across the globe.

Bodh Gaya is a success story. But other sacred sites are still

in peril.

More

about this artwork: After attaining enlightenment, the Buddha

spent seven weeks in meditating in Bodh Gaya and deciding how to

spread his teaching. His first disciples, some traditions believe,

also instantly achieved enlightenment. Many pilgrims have traveled

to this sacred site hoping that they too will become among the 1,002

worshipers that some forms of Buddhism claim will find nirvana at

Bodh Gaya. About 900 years ago a devout pilgrim bought this model

of the main temple at Bodh Gaya and brought it to his or her home

inTibet as a devotional object. More

about this artwork: After attaining enlightenment, the Buddha

spent seven weeks in meditating in Bodh Gaya and deciding how to

spread his teaching. His first disciples, some traditions believe,

also instantly achieved enlightenment. Many pilgrims have traveled

to this sacred site hoping that they too will become among the 1,002

worshipers that some forms of Buddhism claim will find nirvana at

Bodh Gaya. About 900 years ago a devout pilgrim bought this model

of the main temple at Bodh Gaya and brought it to his or her home

inTibet as a devotional object.

Around 250 B.C. the Emperor Ashoka, who ruled much of India, built

a grand complex at Bodh Gaya. It was rebuilt in the second century

A.D. and later repaired in the eleventh century by Burmese Buddhists.

Because of this, the central Mahabodhi temple resembles a Burmese-style

stupa, which takes the form of a narrow

pyramid.

Stupas have been erected throughout the Buddhist world, and many

contain relics of the Historical Buddha or great teachers and saints;

they also remind believers of the Buddha’s enlightenment and

stand as symbols of his teachings. The first stupas in India had

a square base, a round central section, and an umbrella form at

top. A pole that passes through the center links the relics to the

heavens and the earth. In China, Japan, and Korea, the stupa evolved

into the pagoda, and in some traditions,

small stupas are included in personal altars.

Model of Bodh

Gaya

Schist

India, 11-12th century

Pacific Asia Museum Collection

Gift of David Kamansky in honor of Richard Kelton

Bodh Gaya today

Photograph by Don Farber

1. Earliest Images of the Buddha: Afghanistan

Why do some of the oldest existing images of the Buddha have

European facial features and appear to be wearing togas?

The

Emperor Ashoka, who built what are among the earliest surviving

Buddhist monuments in the third century B.C., sent missionaries

throughout India. Other disciples followed existing trade routes

that stretched across Central Asia. When Buddhism spread north and

west to what are now Pakistan, and Afghanistan, it encountered traditions

of depicting holy figures in human form that came from Greece by

way of Alexander the Great’s armies in the fourth century

B.C. The

Emperor Ashoka, who built what are among the earliest surviving

Buddhist monuments in the third century B.C., sent missionaries

throughout India. Other disciples followed existing trade routes

that stretched across Central Asia. When Buddhism spread north and

west to what are now Pakistan, and Afghanistan, it encountered traditions

of depicting holy figures in human form that came from Greece by

way of Alexander the Great’s armies in the fourth century

B.C.

The valley of Bamiyan, Afghanistan, housed one of the largest Buddhist

centers in Central Asia, including the world’s largest standing

images of the Buddha, built during the second and third centuries

A.D. The earlier smaller Buddha, which stood 136 feet high, wore

robes that resembled Greek or Roman robes, but the larger (186 feet)

Buddha had a more Indian appearance.

Buddhism more or less disappeared from the area in the eleventh

century A.D. The two carvings of the Buddha were destroyed by the

fundamentalist Islamic Taliban in spring 2001, to the great horror

of the world community.

More

about this artwork: This head of the Buddha is an example

of the earliest images of the Buddha in human form, dating from

around the 3rd century AD. It was made in the region of Gandhara,

which is in modern Pakistan, Afghanistan, and northwestern India.

Buddhist sculptures from Gandhara, mostly carved from stone or formed

in clay and coated with stucco, were heavily influenced by Greek

and Roman sculpture, so it displays many Western features. These

images generally have European noses and eyes, their clothing often

resembles Roman togas, and their hair is usually wavy. Here, the

Buddha appears to have his hair tied up in a bun, a princely hairstyle

that may have been the origin of the ushnisha,

the bump on the Buddha's head that has come to symbolize the Buddha's

great spiritual power. More

about this artwork: This head of the Buddha is an example

of the earliest images of the Buddha in human form, dating from

around the 3rd century AD. It was made in the region of Gandhara,

which is in modern Pakistan, Afghanistan, and northwestern India.

Buddhist sculptures from Gandhara, mostly carved from stone or formed

in clay and coated with stucco, were heavily influenced by Greek

and Roman sculpture, so it displays many Western features. These

images generally have European noses and eyes, their clothing often

resembles Roman togas, and their hair is usually wavy. Here, the

Buddha appears to have his hair tied up in a bun, a princely hairstyle

that may have been the origin of the ushnisha,

the bump on the Buddha's head that has come to symbolize the Buddha's

great spiritual power.

The Chinese monk Xuanzang, who traveled to India and back to China

in the seventh century A.D to learn the true teachings of the Buddha,

noted that the two large Buddhas at Bamiyan were gilded and brightly

painted red and blue. More than 20,000 caves had been etched into

the high walls of the cliffs into which the figures were carved,

some decorated with paintings, all from the tradition of Mahayana

Buddhism. Many of these have been destroyed or removed and housed

in private collections and museums around the world.

Bamiyan is a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

Head

of the Buddha

Gandhara (Afghanistan/Pakistan), c.3rd century

AD

Stucco

Pacific Asia Museum Collection

Gift of Dr. Paul Sherbert, 93.41.1

Large Buddha

Bamiyan, Afghanistan, before it was destroyed in 2001

2. Two Thousand Years of Buddhism: Sri Lanka

Buddhism

may have vanished from India, but it has been practiced in Sri Lanka,

south of India, for more than two thousand years. Legend proudly

claims that the Buddha himself brought his teachings to the island.

Theravada

Buddhism is still practiced in Sri Lanka today. Buddhism

may have vanished from India, but it has been practiced in Sri Lanka,

south of India, for more than two thousand years. Legend proudly

claims that the Buddha himself brought his teachings to the island.

Theravada

Buddhism is still practiced in Sri Lanka today.

In the twelfth century a king had large stone statues carved of

the Historical

Buddha, and built palaces, gardens, and monasteries at his capital

at Polonnaruwa. The serenity and pose of one of the large Buddhas

is echoed in a small stone Buddha in the museum’s collection

carved during the same era.

More

about this artwork: This stone figure of the Buddha seated

in a meditation pose is representative of Buddha images from Sri

Lanka, where Buddhism, principally the Theravada

tradition, has been practiced for more than two thousand years.

Buddhist art in Sri Lanka has focused on the life of the Buddha

and on events in his previous lives as a bodhisattva. More

about this artwork: This stone figure of the Buddha seated

in a meditation pose is representative of Buddha images from Sri

Lanka, where Buddhism, principally the Theravada

tradition, has been practiced for more than two thousand years.

Buddhist art in Sri Lanka has focused on the life of the Buddha

and on events in his previous lives as a bodhisattva.

Many Sri Lankan figures are carved from stone or cast in bronze

and then gilded. This Buddha is seated in the meditation pose with

his hands together on his lap. He has an erect back and his eyes

look straight ahead, a posture that is common in Sri Lankan images

of the Buddha. The gentle features and simple treatment of the Buddha's

robe, which clings to his form, are also characteristic.

Two hundred years after the Buddha reached enlightenment under

the Bodhi tree, a disciple brought a cutting from it and planted

it in Sri Lanka, where a descendant of the tree flourishes today.

Among the monumental figures at Gal Vihara, the northern monastery

at Polunnaruwa, is a carving of the Buddha lying on his side at

the moment of his final enlightenment. Carved from a rock outcrop

in the twelfth century, the grain of the rock flows gently along

the length of the Buddha’s body.

Seated Buddha

Sri Lanka, 12th century

Stone

Pacific Asia Museum Collection

Gift of Mark Phillips and Iuliana Phillips, 2001.56.62

Recumbent Buddha

Polunnaruwa, Sri Lanka

3. God-Kings of Khmer: Cambodia

In Cambodia, Buddhism and Hinduism were practiced side by

side for a thousand years. The Angkor temple complex, built by the

Khmer emperors between the ninth and twelfth centuries mixes Hindu

and Buddhist architecture and imagery and includes monuments dedicated

to both Mahayana

and Theravada

forms of Buddhism.

The

Bayon, a temple built in central Cambodia by the Khmer people to

represent the cosmic mountain Meru at the center of the Hindu and

Buddhist universe, also served as a three-dimensional mandala--but

only for the Khmer emperors who built it. Around two hundred faces

of the bodhisattva Avalokiteshvara

look out in all directions from the temple’s towers. They

are said to be carved in the image of the god-king Jayavarman VII. The

Bayon, a temple built in central Cambodia by the Khmer people to

represent the cosmic mountain Meru at the center of the Hindu and

Buddhist universe, also served as a three-dimensional mandala--but

only for the Khmer emperors who built it. Around two hundred faces

of the bodhisattva Avalokiteshvara

look out in all directions from the temple’s towers. They

are said to be carved in the image of the god-king Jayavarman VII.

This small sculpture shows many features typical of the Buddhist

sculpture of the Khmer kingdom of Cambodia, in particular the broad

face and the full, sensuous lips.

Conflict in the late twentieth century damaged portions of the

Angkor complex and made preservation difficult. The area’s

dense jungle has reclaimed parts of Angkor cleared by French archaeologists

in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.

Angkor is a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

More

about this artwork: This image shows the Buddha being sheltered

by Muchalinda, the King of the Naga Serpents, a depiction that is

popular in Cambodia, where Buddhism has been practiced from around

the middle of the first millennium. The crown-like hairstyle with

the triangular pointed ushnisha,

or cranial bump, is also typical of Khmer images. More

about this artwork: This image shows the Buddha being sheltered

by Muchalinda, the King of the Naga Serpents, a depiction that is

popular in Cambodia, where Buddhism has been practiced from around

the middle of the first millennium. The crown-like hairstyle with

the triangular pointed ushnisha,

or cranial bump, is also typical of Khmer images.

According to Buddhist legend, while the Buddha was meditating,

a powerful storm struck. Muchalinda, a cobra with seven heads, coiled

himself around the Buddha and stretched his hoods out to form an

umbrella over the Buddha's head to shelter him from the rains. Such

images of the Buddha are particularly common Theravada

Buddhist cultures, particularly in Thailand and Cambodia, where

moments in the life of the Historical Buddha

are given great importance. These cultures also revere snakes and

see Muchalinda’s protection of Buddha as a protective act

to imitate and honor.

Torso of the

Buddha Sheltered by Muchalinda

Khmer, Cambodia, 13th century

Stone

Pacific Asia Museum Collection

Gift of Hans and Margot Ries, 1984.96.1

Head of Avalokiteshvara

The Bayon, Angor Wat, Cambodia

4. Uniquely Thai

Originally an outpost of the Khmer empire, Sukhothai in Thailand

became the capital of the Thai state and flourished from the mid-thirteenth

to the late fourteenth centuries. Wooden palaces built in the complex

have crumbled, while stone stu pas

and monumental statues of the Buddha have survived. In the 1970s,

the United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization

(UNESCO) began a restoration of Sukhothai that continued into the

1980s. pas

and monumental statues of the Buddha have survived. In the 1970s,

the United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization

(UNESCO) began a restoration of Sukhothai that continued into the

1980s.

Purely Thai Buddhist styles were first seen at Sukhothai, including

the Walking Buddha. Unique to Thailand and Laos, the Walking Buddha,

his hand raised in a gesture of fearlessness, is sometimes called

“the placing of the Buddha’s footprint.” The Buddha’s

footprints often bear symbols and signs of the Buddha and the Wheel

of the Law.

This Thai bronze image of the Buddha has many features that are

typical of Thai Buddhist figures from the Sukhothai. Both Buddha

and bodhisattva images have elongated faces and graceful, willowy

bodies.

More

about this artwork: In some cases, the Buddha is actually

depicted walking, a posture unique to Thai images. In addition,

the ushnisha,

or lump on the Buddha's head is stretched upwards and ends in the

shape of a flame, another feature that is unique to Thai Buddha

images. The facial features are also very stylized and curvilinear,

with the eyebrows often meeting the line of the nose. This particular

image also has eyes that are inlaid with shell. Because this sculpture

depicts the Buddha with his eyes open, it originally may have been

a Walking Buddha. More

about this artwork: In some cases, the Buddha is actually

depicted walking, a posture unique to Thai images. In addition,

the ushnisha,

or lump on the Buddha's head is stretched upwards and ends in the

shape of a flame, another feature that is unique to Thai Buddha

images. The facial features are also very stylized and curvilinear,

with the eyebrows often meeting the line of the nose. This particular

image also has eyes that are inlaid with shell. Because this sculpture

depicts the Buddha with his eyes open, it originally may have been

a Walking Buddha.

Thailand is one of the Asian cultures that adopted Theravada

Buddhism, a tradition that was transmitted to areas of Southeast

Asia by monks from Sri Lanka around the middle of the first millennium.

Torso of a Standing

Buddha

Thailand, c.15th century

Bronze

Pacific Asia Museum Collection

Gift of Mr. Edward Nagel, 1984.90.8

Standing Buddha

Sukhothai, Thailand

5. Modern Sites: Vietnam

Some Buddhist sites are important because they are relics

of ancient cultures. Others remind us of more recent events. The

Thein Mu Pagoda in Hue, Vietnam, was the home of Thich Quang Duc,

who burned himself to death in 1963 to protest the Vietnamese government’s

persecution of Buddhists. Although self-destruction is against the

deepest beliefs of the Buddhist faith, Thich Quang Duc’s self-immolation

brought world attention to the United States’ support of a

corrupt and intolerant government.

The

Thien Mu Pagoda had long been the hub of intellectual and political

Buddhist activity in Vietnam. It was constructed in 1844 on the

site of a religious center founded in the seventeenth century. It

is sometimes called the Sacred Lady temple because legend has it

that the governor of Hue had a vision of an old woman telling him

that the site had supernatural powers. The

Thien Mu Pagoda had long been the hub of intellectual and political

Buddhist activity in Vietnam. It was constructed in 1844 on the

site of a religious center founded in the seventeenth century. It

is sometimes called the Sacred Lady temple because legend has it

that the governor of Hue had a vision of an old woman telling him

that the site had supernatural powers.

Thien Mu is on UNESCO’s World Heritage List.

Although Vietnam is a communist country, many of its people are

Mahayana

Buddhists and regularly visit the nation’s temples and worship

images such as this figure.

More

about this artwork: This seated Buddha is a good example

of Vietnamese lacquered Buddhist images. Buddha, bodhisattva, and

monk figures are first carved in wood and then coated with layers

of colored lacquer to make them water, heat and insect resistant

as well as colorful. Vietnamese Buddhist lacquered wood figures

tend to be simple in detail and generally have calm, sweet facial

expressions. His ushnisha,

or cranial bump, is also very pronounced, rising out as a copper

mound from among curls of hair. More

about this artwork: This seated Buddha is a good example

of Vietnamese lacquered Buddhist images. Buddha, bodhisattva, and

monk figures are first carved in wood and then coated with layers

of colored lacquer to make them water, heat and insect resistant

as well as colorful. Vietnamese Buddhist lacquered wood figures

tend to be simple in detail and generally have calm, sweet facial

expressions. His ushnisha,

or cranial bump, is also very pronounced, rising out as a copper

mound from among curls of hair.

Seated Buddha

Vietnam, 19th century

Lacquered wood

Pacific Asia Museum Collection

Museum Purchase with funds from the Bressler Foundation, 1996.28.2

Thien Mu Pagoda

Hue, Vietnam

6. Golden Glory of Burma

Burma (Myanmar) first embraced Buddhism around the middle

of the first millennium, following the Mahayana

tradition and then becoming a Theravada

Buddhist kingdom. As in many kingdoms, the form of Buddhist practice

spread in Burma from the king to his followers. This complex was

built by the kings of Pagan, who flourished in what is now Myanmar

from the middle of the eleventh to the end of the thirteenth centuries,

when Kublai Khan overran the kingdom.

The

Ananda temple is named for one of Buddha’s chief disciples

and represents the infinite wisdom of the Buddha. Built in the early

twelfth century of brick, it is covered in gold leaf. The

Ananda temple is named for one of Buddha’s chief disciples

and represents the infinite wisdom of the Buddha. Built in the early

twelfth century of brick, it is covered in gold leaf.

Unlike most Theravada Buddha images, which have a humble, monk-like

appearance, many Burmese Buddha images are decorated with crowns,

jewelry, and an unusually tall cranial bump, or ushnisha.

More

about this artwork: The elaborate Burmese style developed

around the 14th century, in part under the influence of the intricate

Buddhist imagery from East India's Pala kingdom. However, such crowned

figures of the Buddha are also said to depict a moment in the life

of the Buddha, when he took on the form of the Universal Monarch,

with a crown, jewels and a beautiful throne, to impress an earthly

king and lead him to Buddhism. As in this image, his sits with one

hand in the Earth

Touching Gesture at the moment of enlightenment. His face is

very round and he has a gentle, sweet expression that is also typical

of Burmese images of the Buddha. More

about this artwork: The elaborate Burmese style developed

around the 14th century, in part under the influence of the intricate

Buddhist imagery from East India's Pala kingdom. However, such crowned

figures of the Buddha are also said to depict a moment in the life

of the Buddha, when he took on the form of the Universal Monarch,

with a crown, jewels and a beautiful throne, to impress an earthly

king and lead him to Buddhism. As in this image, his sits with one

hand in the Earth

Touching Gesture at the moment of enlightenment. His face is

very round and he has a gentle, sweet expression that is also typical

of Burmese images of the Buddha.

Crowned Buddha

Burma (Myanmar), 19th century

Lacquered and gilded wood

Pacific Asia Museum Collection

Gift of Union Bank of California, 2001.25.1

Ananda Temple

Pagan, Burma (Myanmar)

7. China’s Long Legacy

Throughout Asia, Buddhist leaders built many monumental testimonies

to their faith: huge temple complexes, towering statues, precious

building materials. The Longmen cave temples in Henan province,

China, have to be some of the most impressive. Begun at the end

of the fifth century, the project continued without a break for

four hundred years by Buddhist rulers of the Northern Wei and Tang

dynasties.

Generations

of sculptors carved statues of the Buddha, bodhisattvas, and guardian

figures from limestone, adding inscriptions that honor patrons.

The Empress Wu (reign 690-705) is commemorated, legend goes, in

the face of the Cosmic Buddha. Generations

of sculptors carved statues of the Buddha, bodhisattvas, and guardian

figures from limestone, adding inscriptions that honor patrons.

The Empress Wu (reign 690-705) is commemorated, legend goes, in

the face of the Cosmic Buddha.

Buddhism first arrived in China around the first century AD along

the Silk Road and was eventually the largest Asian nation to adopt

the faith. Over the centuries, Buddhism and its arts enjoyed periods

of glory and decline under the nations various rulers.

This

bronze figure dates to the Ming dynasty (1368-1644), when Chinese

Buddhism was influenced by Tibetan Buddhism. This

bronze figure dates to the Ming dynasty (1368-1644), when Chinese

Buddhism was influenced by Tibetan Buddhism.

More about this artwork: This bronze

figure shows traditional Chinese features, such as the fleshy cheeks,

the highly stylized and linear facial features, and the ornate patterning

on the borders of his robes. The toga-like folds of the robes and

the leggings recall the Buddha figures of Gandahar. Unlike more

meditative statues, this Buddha holds its hand aloft in a gesture

of fearlessness.

Figurine of the

Buddha

China, Tang dynasty (618-906 AD)

Bronze and gilt

Pacific Asia Museum Collection

Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Joseph Kamansky, 1991.70.2

Longmen Caves

Henan Province, China

8. A Perfect Place: Tibet

A mandala is a model or a map of a perfected environment,

most often a symbolic depiction of the world of a Buddhist deity.

Mandalas are used by Vajrayana Buddhists

of Tibet and Mahayana Buddhists to

practice concentration and to cultivate inner vision, picturing

themselves present within the perfected environment. From here,

the deity can help them to progress towards a perfected state of

enlightenment.

Tibetan

mandalas can be painted, printed, embroidered, or created in sand,

often in the floor plan of a palace; sometimes three-dimensional

mandalas are constructed. Tibetan

mandalas can be painted, printed, embroidered, or created in sand,

often in the floor plan of a palace; sometimes three-dimensional

mandalas are constructed.

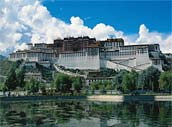

The Potala Palace in Lhasa, Tibet, is part city hall, fortress,

and monastery and, until 1959 when the Chinese took control of Tibet,

it served as the home of the Dalai Lama. Work began on the palace

in 1645 under the Fifth Dalai Lama and was concluded in 1695. It

was named after Potalaka, the Buddhist paradise (or pure land) of

the compassionate bodhisattva Avalokiteshvara.

More

about these images: This particular mandala depicts the sacred

abode, or perfected environment, of the Buddha, who sits in the

lower right-hand corner of the mandala, and four bodhisattvas. Inside

the circle are structures showing the four main gates and the floor

plan of the sacred space. Also inside are lotuses, clouds, and vajras. More

about these images: This particular mandala depicts the sacred

abode, or perfected environment, of the Buddha, who sits in the

lower right-hand corner of the mandala, and four bodhisattvas. Inside

the circle are structures showing the four main gates and the floor

plan of the sacred space. Also inside are lotuses, clouds, and vajras.

The grandeur of the Potala Palace owes much to its hilltop location

and its formidable appearance. Its powerful appearance symbolizes

the union of the spiritual and the political, and it serves as a

symbol to the Tibetan people of the Dalai Lama’s authority

even in exile.

Painting of a Buddhist

Mandala

Tibet, 18th century,

Ink and gold on paper

Pacific Asia Museum Collection

Estate of Mr. and Mrs. Wilmont Gordon, 1990.14.57

Potala Palace

Lhasa, Tibet

|

![]()